Water on Earth

“The Rich

get richer, as the Poor get poorer”

As

the Earth warmed up, the global water cycle speeded up. This

means that, compared to a few years back, more water passes

through each stage of the cycle—evaporation from warmer

oceans, condensation in clouds, rainfall, snowfall, and river

flows. Where it is already wet, the climate becomes wetter,

and floods more frequent; and where it is already dry, the climate

becomes drier, and drought more common. The laws of physics

that govern meteorology anticipate a speedup, but observing

whether it is happening is difficult. (See How the water

cycle kicked into high gear, below.)

Paul Durack and his Australian

team reported1 in Science

that the geographic patterns of salinity in the world’s

oceans are now more pronounced: salty regions became saltier,

and less salty regions became fresher. From their study, they

concluded that the water cycle on Earth accelerated by 8% per

degree of global warming over the 50 years from 1950 to 2000.

The distribution of salt in the ocean was linked to where evaporation

or precipitation had increased; wherever salinity of seawater

increased, the net evaporation had increased, but where salinity

decreased, more rain had fallen recently than before.

Durack also wrote, “the

‘rich get richer’ mechanism is already operating,

with fresh regions becoming fresher and salty regions saltier

in response to observed warming.” The observed speedup

of the water cycle is “double the response projected by

current-generation climate models, and suggests that a substantial

(16 to 24%) intensification of the global water cycle will occur”

in a world that will be 2° to 3°C warmer.

Uncertain availability of

fresh water is a greater risk to human society than is warming

by itself, the authors add. The United States is grappling with

a widespread drought this summer as severe as the historic drought

of the 1950s (story, upper right). The message from climate

scientists may soon be sinking into the nation’s consciousness.

_____________________________________

CITATIONS:

1.

“Ocean

salinities reveal strong global water cycle intensification

during 1950 to 2000” by Paul J. Durack, Susan E. Wijffels,

and R. J. Matear, Science, v. 336,

455 (27 April 2012).

|

Over

55% of USA Now in Drought

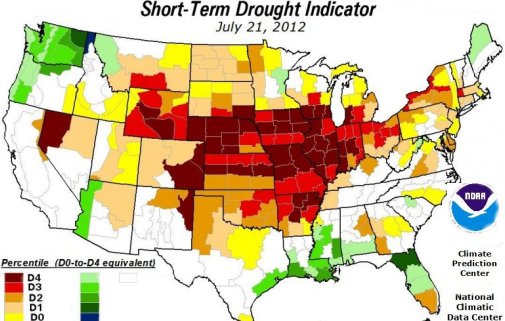

The

central Midwest of the United States is experiencing a widespread

but short-term drought, that threatens the nation's supply of

food and animal feed in this growing season. By the third week

of July, some 55% of the land area of the US was in moderate drought

or worse (tan color, above), and the area continues to increase.

The affected area is the greatest since 1956, fifty-six years

ago. On the map, 38% of the nation is in severe drought (category

D2, orange) or worse, and 17% in extreme drought (category D3—red)

or worse. At this writing, all forecasts anticipate that the drought

will continue through this October, according to the US

Seasonal Drought Outlook, of the US Climate Prediction Center.

The

US Department of Agriculture (USDA) reported that 55 percent of

the pasture and rangeland was in poor to very poor condition in

the US. In the Plains and Midwest states, crop losses mounted,

ranchers liquidated herds, and trees continued to drop leaves

and branches. On July 25, the USDA designated even more drought

disaster areas, bringing the total for the 2012 crop year to 1369

counties in 31 states.

And

with more than 40% of US agricultural land now in extreme

or exceptional drought, “Prices of both corn and

soybeans soared to all-time highs, . . with corn climbing more

than 50 percent in the past four weeks alone due to the worsening

drought, squeezing ethanol and livestock producer margins.”

(Reuters, July 20, 2012)

|

|

How water cycle

kicked into high gear

Evaporation of water

increases 7% for every degree C that

water is warmer, according to the laws of physical science.

As the ocean heats up, its molecules speed up, and more

of them leave the ocean surface every second. Driven by

evaporation from the oceans, the entire water cycle speeds

up. Rates of evaporation, condensation of water vapor

into cloud droplets, and precipitation from clouds have

all speeded up since 1950.

As

ocean water evaporates, it leaves behind salt. In the

hot subtropics where the sky is clear, the evaporation

is intense, and the salinity of the ocean, already high,

has increased. But wherever rainfall is abundant, the

salinity has been decreasing – likely because greater

rainfall has diluted the ocean with more fresh water than

before.

It

is important to subtract the precipitation from the evaporation

over oceans, when estimating the global water budget.

The difference—which is called “net evaporation”—does

appear to be increasing globally as the temperature of

the Earth climbs. Precipitation itself seems to increase

more slowly, at about 3% per degree C of warming. |

|

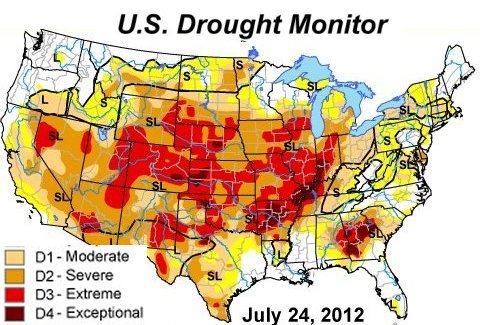

The

first map above assesses the short term drought impacts for about

six months or one growing season. The Drought

Monitor product

of the University of Nebraska at Lincoln, widely used since

2000, attempts to depict both short- and long-term severity and

impacts of drought. Its depiction for the same time (next image,

below), shows areas of extreme (D3) and exceptional

(D4) drought (in red and maroon colors) in Arizona, New Mexico,

and Georgia. The short-term depiction above does not depict such

extreme categories of drought in the three states. A glance at

the long-term drought assessment, next.

|

|

|

|