First

Time Ozone Hole

Formed in the Arctic

In 2011, for the first time, ozone was destroyed over the Arctic

regions to an extent comparable to yearly losses in Antarctica.

Although Arctic temperatures are milder than the severe cold

of the Antarctic stratosphere, a comparable percentage of ozone

was destroyed in both polar regions this year. Writing in Nature,1 Gloria L. Manney and 28 co-authors

claim that a true “ozone hole” formed over the Northern

Hemisphere this year.

|

|

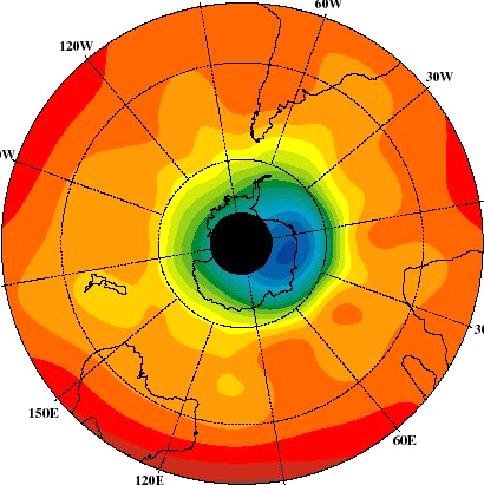

Picture above depicts the Ozone

Hole over Antarctica. From 1979 to 1997, total ozone levels

in the atmosphere declined 40% or more in the blue-toned region.

|

In the 1980s, scientists were stunned to discover that a “hole”

formed in the ozone layer of the stratosphere every spring over

Antarctica. They were quickly convinced that the newfound ozone

disappearance was real. Chlorine compounds were destroying the

natural ozone, and the only known source of chlorine was a class

of man-made chemicals called chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), which

were manufactured as refrigerants and as propellants in aerosol

spray cans.

In the Antarctic stratosphere, temperatures routinely plummet

to an extremely frigid –80°C by the end of winter. When

that happens, water vapor and nitric acid condense into polar

stratospheric clouds from 15 to 30 km above the ground. The cloud

particles offer surfaces on which chemical reactions, involving

chlorine, can be catalyzed. These reactions decompose ozone in

the atmosphere.

Scientists were not sure that an ozone hole would form in the

Arctic, since the Arctic stratosphere rarely gets cold enough

for these clouds to form, although they did observe that some

ozone was lost every year. Manney’s team reports that the

whirl of air around the Arctic known as the “polar vortex”

was unusually cold and isolated from surrounding regions for four

months ending in March 2011. That isolation was enough to destroy

most of the ozone there by March—which was unprecedented

in the Northern Hemisphere. |

|

While the greenhouse effect warms the lower atmosphere, it actually

cools the stratosphere. That is because greenhouse gases intercept

some of the heat radiation that Earth emits to outer space. That

energy warms the lower layers, but what the low layers gain, the

upper layers lose. So the stratosphere has been steadily cooling

for several decades precisely because the greenhouse effect has

become stronger.

Thus, with ever more global warming at the surface, a very cold

stratosphere like the one in 2011 may occur more often, which

would favor future Arctic ozone holes. With some concern, the

authors conclude that an ozone hole in the north “could

exacerbate biological risks from increased exposure” to

ultraviolet radiation, especially when the polar vortex shifts

over populated middle latitudes, as it did last April.

Citation:

1. “Unprecedented

Arctic ozone loss in 2011” by Gloria L. Manney and 28

others (2011). Nature, vol. 478, 469–475, 27 Oct.

2011, doi:10.1038/nature10556.

|

|