Earthquake during El Niño led to rapid spead of

Zika epidemic

Health

care became dysfunctional; a harbinger of natural disasters

on a warmer Earth

|

|

Nearly seven thousand

persons became infected with the Zika virus soon

after a large (magnitude 7.8) earthquake ravaged coastal

Ecuador in 2016. A Latin American team of scientists led

by Cecilia Sorensen, MD at the University of Colorado, conclude that a strong El Niño at the time combined

with the devastated infrastructure and a breakdown of social

structures to propel a widespread epidemic of Zika virus

(citation 1). The quake and the epidemic

coincided with a strong El Niño, a natural climate

anomaly that brings unusually warm and humid air and heavy

rainfall to the Pacific coast of South America. The “steam-bath”

atmosphere greatly accelerated the spread of Zika.

The

quake killed 660 people, displaced 9,700 people, damaged

9750 buildings, and put 720,000 people in need of humanitarian

assistance (2). It savaged the health

care and sanitation infrastructure, and forced people to

massively migrate into the cities (3).

(continues, below

left)

|

| El

Niño and its opposite, La Niña, together are

a natural climate variation that appears from time to time

over the last few thousands of years. Each time the local

weather/ seasonal climate are altered anywhere from a few

months to two years. On the west coast of South America,

El Niño brings high temperatures and humidity, and

rainfall well above normal. Whether or not a climate variation

is natural (an “unnatural” variation might be one caused

by human influences), the different weather conditions can

promote illness or make it difficult for a society to recover

from a natural disaster. (The plight of Puerto

Rico after hurricane Maria breezed through in September

2017 comes to mind.)

The

quake hit Ecuador only three months after the Zika virus

arrived in there in 2016, and El Niño was already

in progress. Mosquitoes, specifically the species Aedes

aegypti, transmit the Zika virus from person to person.

This same mosquito also carries the viruses that sicken

people with Dengue fever and Chikungunya fever. |

|

Sorensen's

team asserts that the “social vulnerability” of that region

made the health crisis unmanageable. The Intergovernmental

Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) defines social vulnerability

as the degree that a country cannot adapt to any external

change by altering its practices to offset potential damages.

In Ecuador, poor housing, the lack of piped water in homes,

and the marginal health care system allowed the mosquito

population to explode and spread the Zika virus quickly.

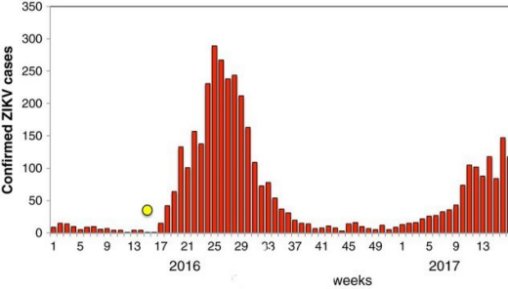

The bar graph at the right shows how quickly the illness

spread: from zero to ten cases cases before the quake,

to 300 cases ten weeks later. After the quake, people

slept outdoors where they felt safe but were exposed to

mosquito bites. With no running water piped into their

homes, people stored water in open cisterns where mosquito

larvae breed.

The

short-term climate conditions that El Niño ushered

in -- warmer temperatures at night, high humidity, and

heavy rainfall – fostered an explosion of mosquitoes.

Health officials had already blamed such conditions for

the rapid spread of Dengue fever by the same species of

mosquito. Because there were always more cases of Dengue

fever than of Zika, the health of the population and the

ability of the health care system to deal with it were

already strained by the Dengue fever epidemic.

|

Above: The confirmed number of cases

of Zika in Ecuador, for every week in 2016 and part of 2017.The

yellow circle marks the week of the earthquake in April

2016. (Data from Ecuadorian Ministry of Public Health.) |

Sorenson

does not attribute the spread of Zika to global climate

change. The anomalous weather during El Niño is

temporary and natural. However, she points out that global

climate is currently taking a direction toward warmer

and wetter conditions that are known to boost the spread

of infectious diseases.

Areas that are already stressed by short-term climate

changes like El Niño can be sent over the edge

by a natural catastrophe. The bottom line is that we would

be wise to prepare in advance for a health crisis when

a natural disaster strikes during anomalous climatic conditions,

especially in a region “socially vulnerable” to disasters.

When social structures like the police, emergency responders,

and the supply of water and food broke down in Ecuador,

a health crisis spiraled out of control. In our future

warmer climate on Earth, extreme weather, especially extreme

rainfall, are predicted to become more frequent. What

would the consequences be? Serious humanitarian crises

after natural disasters.

The authors recommend practices for society to prepare

for a difficult future in health care. They encompass

greater cooperation between sectors of society that deal

with disasters: the health care industry, the government,

the research enterprise, and the emergency response folks.

|

News

Forthcoming -- in November

-

The record hurricane season of 2017 in North America

and the Atlantic: what was different this year?

-

Are grass-fed cattle really better for the climate

than those on feedlots?

-

The last remnant of the Ice Age in North America

is about to disappear

|

| CITATIONS:

1.

“Climate

Variability,Vulnerability, and Natural Disasters: A

Case Study of Zika Virus in Manabi, Ecuador Following the

2016 Earthquake” by Cecilia J. Sorensen , M J. Borbor-Cordova,

E. Calvello-Hynes, A Diaz, J. Lemery, and A. Stewart-Ibarra.

GeoHealth, vol. 1.

(Early View Article published online before inclusion

in a journal issue) –------ available with open access at:

https://doi.org/10.1002/2017GH000104.

2. Pan American Health Organization (2016): “The Earthquake

in Ecuador: Significant damage to health facilities; emergency

medical teams deployed.” Disasters, World Health Organization/Pan

American Health Organization, June 2016, vol. 121,

1-3.

3.

United States Agency for International Development (USAID,

2016): “Ecuador

- Earthquake.” Fact sheet #5, Fiscal year 2016.

| |

|