|

A

New Normal: Frequent Catastrophic Flooding

|

|

When its two rivers

flooded, Calgary, Alberta had to evacuate its entire downtown

area on June 21 of this year. That flooding caused three deaths

and the displacement of over 100,000 people in the Canadian

province (from the Minneapolis Star-Tribune). (See

story below, “A record wet spring

of 2013.”)

“FDR dispatched

thousands of relief workers. In a landscape fraught with dangers—from

unmoored gas tanks that became floating bombs to powerful

currents of filthy floodwaters that swept away whole towns—people

hastily raised sandbag barricades, piled into overloaded rowboats,

and marveled at water that stretched as far as the eye could

see.

“The overflow

surpassed all estimations of the Ohio's potential strength.

At one point the river's entire 981-mile run stood above flood

stage. Buildings, farms, and cities . . . disappeared beneath

the waves. Water covered 15,000 miles of highway. . . . .

. . . Hundreds of people drowned or died from pneumonia and

other illnesses.”

(From

the book, “The Thousand-Year Flood”

by David Welky (1).) more

|

| A

100-year flood is expected once in a century, by definition —

but that is true for the 20th century when climate statistics

were compiled. As the climate warms and the wet or dry patterns

of rainfall change, hydrologists are revising predictions for

how often a serious river flood of this magnitude might recur

in the 21st century. A new estimate (2) published

in Nature Climate Change by Y. Hirabayashi and his team

at the University of Tokyo predicts that a current 100-year flood

will recur much more frequently later this century (from 2070

to 2100) in much of south and southeast Asia, wet equatorial Africa,

eastern Siberia, the northern Andes, and the intensive farm belts

of Argentina and Brazil. Their prediction of more frequent river

flooding is robust for areas influenced by the Asian summer monsoon

(southern India, Indochina and southern China), and for the farm

belts in South America. Hirabayashi’s team calculated that

a current “100-year flood” can be expected to recur

every 10 to 20 years (about five times more frequently than now)

in some regions. |

|

|

In

contrast, they predict a drier climate and less frequent flooding

in most of Europe, the central states and southern Rocky Mountains

of the USA, central Asia from Turkey to Pakistan, and far southern

South America. For example, the Danube River basin in Europe

is projected to dry out: a 100-year flood would recur only about

every 250 years in the new climate. more

|

A Swiss-Austrian

team finds that until 2020, there is a "window"

of greenhouse gas emissions that would still limit global

warming to 2°C over the long term. That window does

not stay open for long. Story

here. |

|

We refer only to floods on rivers, not coastal flooding caused

by storm surge or battering waves on a seashore. A once-in-a-century

river flood is said to have a "return period" of 100 years,

and its magnitude depends on the river's basin, as well as

the local climate. In the years 2070 to 2100, under the most

extreme of four cases of human climate alteration, a current

100-year flood would recur more often on 42% of the world's

land. It would recur less often on another 18% of the land

area. More than half of the climate models predicted this

increase for places where flooding will become more frequent;

that gave the research team more confidence that their prediction

is valid.

Rather than using

a single global climate model linked to a single river runoff

model, Hirabayashi's team assembled results from 11 different

climate models, to gain more confidence in the overall result.

For each model, they obtained simulations that assume four

different pathways for future human emissions of greenhouse

gases. In their summary, they only reported conclusions based

on one pathway leading to the "most dangerous outcomes"

(in their words) for climate: a pathway (3)

in which industrial societies do not limit greenhouse gases

at all before the year 2100.

When the team projected

future return periods for a flood now considered to be a 100-year

event, the various models projected dramatically shorter return

periods for a few rivers: as short as 5 years for the Nile

River, and about 10 years for Africa's Congo, and the Mekong,

Ganges, and Brahmaputra Rivers in Asia.

|

|

Other students of natural disasters

proposed the concept of flood exposure to measure the number

of people living in inundation zones of floods large enough

to have a return period of 100 years in the present climate.

The recent flood exposure of the world's people was 15 million,

for the years 1980-1999. The flood exposure started to rise

in 1996 after remaining flat for many decades.

Keeping the population constant at

what it was in 2005, but allowing climate to change and rivers

to flood more or less often as rainfall patterns changed, Hirabayashi's

team estimated that 27 million people would be exposed to floods

of this size by the year 2100, if the global climate warms by

2°C above the average for 1980-1999. (Two degrees of warming

is the maximum that might avoid "dangerous interference in the

climate," according to many scientific bodies.) And if it should

warm by 6°C, or three times as much, then 93 million people

would be living in the way of such catastrophic floods.

CITATIONS:

1. David Welky,

“The Thousand-Year Flood: The Ohio-Mississippi Disaster

of 1937”, book, 384 pp., © 2011. University

of Chicago Press.

2. “

Global flood risk under climate change,” by Y. Hirabayashi

and colleagues, Nature Climate Change, published

online 9 June 2013, Doi: 10.1038/NCLIMATE1911.

3. These pathways

are termed “representative concentration pathways”

(RCP) and are summarized in: “The

representative concentration pathways: an overview”

by D.P. van Vuuren and 14 colleagues, Climatic Change,

vol. 109, 5-31, Dec. 2011,

DOI: 10.1007/s10584-011-0148-z.

next story (

News headlines)

|

Mekong River in a typical flood

Mekong River in a typical floodA

record wet spring of 2013 in central US

“This is the worst spring I can remember in my 30

years farming. Just continuous rain, not having an opportunity

to plant,” said Rob Korff of Missouri, who planted his

corn a month late because of the weather.” (Minneapolis

Star-Tribune, June 1, 2013).

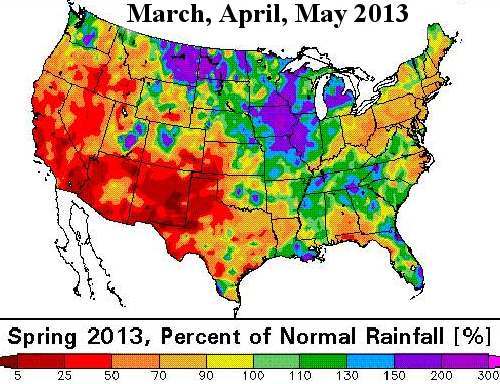

Iowa had its wettest spring ever in

2013 with 18 inches of precipitation, twice the 3-month normal

amount. Very wet conditions were the rule in five other neighboring

states (rainfall map, below).

(From State

of the Climate:

synoptic discussion for May 2013, published online June

2013, NOAA/ National Climatic Data Center.

|

Credit: US National Climatic Data Center

Credit: US National Climatic Data Center

|

|

|